For Noir’s Sake: A Sunbaked Triple

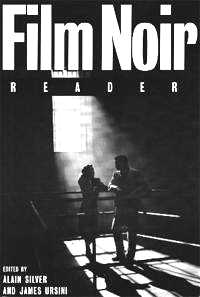

In her eye-opening essay, The Post Noir P.I., initially published in 1996 for the Film Noir Reader (an anthology of compositions I think should be on the bedside table of any fan interested in the genre, by the way), Elizabeth Ward made the case for what became of the private detective story in film during the pivotal decade of the ’70s. It remains the piece of writing on the subject I recommend to anyone who says they enjoy noir, be it written for the page or the cinema.

In her eye-opening essay, The Post Noir P.I., initially published in 1996 for the Film Noir Reader (an anthology of compositions I think should be on the bedside table of any fan interested in the genre, by the way), Elizabeth Ward made the case for what became of the private detective story in film during the pivotal decade of the ’70s. It remains the piece of writing on the subject I recommend to anyone who says they enjoy noir, be it written for the page or the cinema.

The pair of films Ms. Ward spotlighted in her article, and one released a couple of years later that friends have convinced me belonged in the set, went on to show the ‘black film’ (what the term film noir means in French) was not limited to the night, or the black & white world of shadows and high contrast. Or even the ’40s and ’50s.

This summer, I screened the three feature films in succession right after my birthday. And they proved to be a triple-feature tailor-made for the hot season and the dark genre. Not to mention, besides their stellar casts, each film made distinct use of the classic noir setting of Los Angeles as its own unmistakable character. A sun-drenched venue each shamus had to deal with in their noir-inflected stories.

“Film noir has often used the character of the male private investigator to illustrate the alienated and paranoid nature of men in postwar America. As detectives these men become involved in dangerous situations that they feel compelled to control and change while attempting to reestablish morality in a world that appeared to ignore it. After the classic period of film noir, the private detective still remained an occasional protagonist in a traditional mystery film. Only a few times in the post-noir era of the 1960s and 1970s did filmmakers evoke the noir sensibility through the “p.i.”” ~ Elizabeth Ward

How true. Given the amount of upheaval that occurred during the first of half of the 1970s alone, I think those few who tackled the private eye neo noir of the modern motion picture era couldn’t have picked a better time to do it in. Or a more appropriate style to show the disruption in the U.S. that came with it. For those either born later or missed their wake-up call entirely, let’s tick off some of what happened from 1971-75, which covered the span of the three films in question, shall we?:

- the Pentagon Papers were published

- the Watergate Burglary occurred

- the Oil Crisis began

- Nixon released the Watergate Tapes

- the Vietnam War ended

- Nixon resigned

- Gerald Ford pardoned him

- Saigon fell

- New York City was bailed out by the Federal Government

And that was only a smidgen of what happened inside of those five years. When you want to talk disarray, it’s the ’70s that is its poster child, folks. Yes, I’ve called attention and shaded it toward the dark side of things, but that is the subject at hand. By the way, the microprocessor, the foundation of all computing, and just about anything electric these days, was also introduced (along with the floppy disc) early in this same period. Feel better now? Okay then. As I wrote a short while back, covering another venerable genre:

“While I’ve wandered into crime/mystery literature of late, I feel that style of writing has a kinship with the western. Like the venerable oater, crime fiction shares similar core motifs of “love, danger, and death”. Honor and a code of ethics can also be attributed to both. Each of these categories has a tremendous versatility in their morality plays to express a point of view and comment on history and injustice.”

So, what are these movies authors like Elizabeth Ward and Duane Swierczynski think epitomized the “… self-consciousness of the history of film noir”, along with this period of time? A trio of films that symbolized the corruption and disruption that left many feeling powerless, weak, and helpless. In chronological order of their release (though not the order I watched them recently):

“While the detectives of Hickey and Boggs share the independent spirit of their earlier counterparts, they differ in the extent to which they can control their situation. Through ten years, the film noir protagonist had steadily lost any ability to effect change in a modern world, and this increasing powerlessness is a correlative of diminishing social morality. This powerlessness is sardonically expressed by Frank Boggs when he says, “I gotta get a bigger gun. I can’t hit anything.” ~ Elizabeth Ward

This is another of the forgotten crime gems of this decade I’ve commented on more than once on this blog. Written  deftly by Walter Hill and directed by Robert Culp (co-starring with his I, Spy colleague, Bill Cosby) Hickey & Boggs (1972) is likely the least remembered of the set. The essence of the film was the decline and powerlessness of the profession. The private investigator as relic.

deftly by Walter Hill and directed by Robert Culp (co-starring with his I, Spy colleague, Bill Cosby) Hickey & Boggs (1972) is likely the least remembered of the set. The essence of the film was the decline and powerlessness of the profession. The private investigator as relic.

This wasn’t Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade pounding the streets for clues or uncovering corruption in the noble, traditional sense à la Raymond Chandler or Dasheill Hammett. No, the protagonists in this tale are downtrodden like most everyone else was in the ’70s… and living in (perfectly coined by Duane) a “mean, sunbaked” Los Angeles of the time that had little pity for their ilk.

“Like Hickey and Boggs, The Long Goodbye is as much about friendship and betrayal as it is about violence and murder. P.I. Marlowe’s primary purpose is to clear his friend’s name and to help a woman find her disturbed husband, whom he believes she loves very much. As in Hickey and Boggs, there is a vicious gangster, Marty Augustine, looking for the person who took his money. The mystery that ensnares the characters is something that Philip Marlowe stumbles upon. He does not wish to unravel it but cannot help doing so. The 70s Marlowe is a man lost in a world he does not understand.” ~ Elizabeth Ward

Robert Altman’s take on the genre in The Long Goodbye (1973), and especially on this formative character of the literature, pre-dated, by more than a year, what most fans believe was the quintessential neo noir of the latter half of the 20th century: Chinatown. Noah Cross’ immortal quote from that film could have easily been suited for this:

Robert Altman’s take on the genre in The Long Goodbye (1973), and especially on this formative character of the literature, pre-dated, by more than a year, what most fans believe was the quintessential neo noir of the latter half of the 20th century: Chinatown. Noah Cross’ immortal quote from that film could have easily been suited for this:

“You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but, believe me, you don’t.”

Leigh Brackett’s screenplay of Raymond Chandler’s ‘The Long Goodbye’ novel has a dream-like quality to it. This was Marlowe (Elliott Gould) as a Rip Van Winkle-like character waking to a new world, and always playing catch-up.

As Eileen McGarry wrote in her film description for the Film Noir: the Encyclopedia:

As Eileen McGarry wrote in her film description for the Film Noir: the Encyclopedia:

“The chief motivation behind the narrative structure of Night Moves is Harry Moseby’s compulsive “need to know.” But whereas this curiosity, combined with emotional detachment, was Philip Marlowe’s strength, it is Harry’s fatal flaw… The illusion that each can control his or her life, make choices, and impose meaning on other people’s choices, obscures the one truth of their universe: that there is no truth and no amassing of evidence will make any difference.”

This was the paradigm of the post-noir P.I. meeting up with the post-Watergate eon. Arthur Penn, like Altman, gave the genre a modern flavor with this mid-era film, Night Moves (1975), but with an unmistakable ’70s aftertaste. A metaphor for the decade that spawned it.

It remains a hard-boiled mystery, with all of the clues laid about and within easy reach of its principal (Gene Hackman in a role he was born to play). However, inside this anti-detective masterpiece (screenplay by Alan Sharp), you had a protagonist too overwhelmed with his own problems to spot and solve them for his clients.

Even though the film spent a good bit of its tale in the Florida Keys (Key Largo anyone?), as with the other two works, its core still lay in the City of the Angels. All the cynicism, fatalism, and moral ambiguity long tied with the genre felt right at home in this city and its time. Under a bright sunshine that brought its heroes no warmth.

26 Responses to “For Noir’s Sake: A Sunbaked Triple”

Another superb post Michael. As you know I’m a big fan of the genre. Here’s a little piece of info for you. I don’t whether you know or not but Private Detectives was an agency formed by Allan Pinkerton who hailed from my home city of Glasgow. For a genre I love and many books and film’s that are right up my street. I’m always rather surprised that it all stemmed from a Scotsman. I think he was born in “the Gorbals” area of Glasgow, where I used to live myself.

LikeLike

Awesome article once again, Michael. I’m not well-versed in 70s films but I have seems some great ones indeed and Noir is one of my fave genres as well.

Mark, wouldn’t it be nice if they made a film on Allan Pinkerton? Of course I’d love to see GB in the role 😉

LikeLike

I think that’d make a great film Ruth. Butler would indeed be a fine candidate but I’ll go for my buddy, Bobby Carlyle. 😉

LikeLike

I’d could go for this, too. Thanks, Mark.

LikeLike

Thank you very much, Ruth.

p.s., I’d certainly be interested in a Pinkerton film, too.

LikeLike

Thank you, Mark. And, that’s great info. If you’re no longer in Glascow, what area are you now in?

LikeLike

I still live in Glasgow. I just no longer live in the Gorbals area. I live literally minutes from a place called ‘Battlefield’ where Mary Queen of Scots fought a famous battle. Hence the name.

LikeLike

Awesome, Mark. Thanks for the info.

LikeLike

Hi, Michael and company:

Very interesting critique!

‘Hickey and Boggs’ is a very under rated gem. Gets the plight of a couple of L.A. Private Eyes down just about right. While being a nice jumping off point for young talent like Michael Moriarty, in something so not Culp and Cosby from ‘I Spy’.

‘The Long Goodbye’ is in a class by itself. Very 1970s Marlowe. Though a nice counter point is ‘The Big Fix’ from 1978. With Richard Dreyfuss as a contemporary San Francisco private eye who stumbles onto a really big case.

‘Night Moves’ is another low key classic with Gene Hackman taking his Marlowe like character to new heights.

I’m curious as to where Ms. Ward places ‘The Big Combo’ from 1955. A way ahead of its time, little known B&W masterpiece?

LikeLike

Great to hear you’re another fan of H&B, Kevin. It truly is a forgotten gem of a neo noir. I need to check out ‘The Big Fix’ from 1978 and The Big Combo’ from 1955. Thanks for the film recommendations and the comment, my friend.

LikeLike

Fantastic picks! I love all these films dearly and they make for a great downbeat noir triple bill. Honorable mention for best ’70s noir not actually made in that decade: CUTTER’S WAY.

LikeLike

Hi, JD:

Excellent catch with ‘Cutter’s Way’!

A title that slipped under my radar earlier. One of Jeff Bridges’ best early roles. More laid back and far better than his Terry Brogan in ‘Against All Odds’.

LikeLike

CUTTER’S WAY is definitely superior to AGAINST ALL ODDS but I do like that film a lot also, thanks to the presence of James Woods and sexy Rachel Ward!

LikeLike

Yep, CW is better. AAO is definitely an 80s noir. Nothing wrong with that, but a totally different atmosphere. Thanks. J.D.

LikeLike

Ah, yes. The remake of ‘Out of the Past’. I’m with J.D. on this: Woods and Ward make it worth seeing. But, ‘Cutter’s Way’ is the better film. Thanks, Kevin.

LikeLike

I’m with you on ‘Cutter’s Way’, J.D. That film from ’81 did have the 70s noir vibe. Thanks, my friend.

LikeLike

This is terrific, Michael. I haven’t seen any of these, but I am definitely interested in doing so now. I also put in a request for the Film Noir Reader from the library. Thanks!

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Eric. All of these films, along with the FILM NOIR Reader, is worth a visit.

LikeLike

Great post as always. Very informative 😉

LikeLike

Thanks, Fernando :-).

LikeLike

I guess I never realized how perfect the 1970s really were for the film noir…the disillusionment and paranoia fit right in. Ashamed to say that while I’ve seen many of the first noir cycle of films, I’ve never seen these three. I will add them to the queue. Thanks Michael!

LikeLike

Yeah, the period was a distinct one. I hope you can check these films, and get to watch them as a set. They really work quite well together. Many thanks, Paula.

LikeLike

[…] Sunday, finish with Sun-baked Noir triple-feature (hey, it’ll still be shorter than Saturday’s […]

LikeLike

[…] fast against their previous TV character images here in an underappreciated neo-noir that heralded the change for the private eye during this tumultuous […]

LikeLike

[…] crime film has turned many of those I’ve mentioned it to into fans. Joins a couple of other sun-baked neo-noir classics of the same decade that upend the genre of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. This isn’t […]

LikeLike

[…] ball, with their case outcomes being decidedly bitter, even if they solved it. Look no further than the three I highlighted a few years back that illustrated the collision of the venerable “private dicks” of […]

LikeLike